Why You Shouldn't Talk to the Police (Even if You Like the Police). Part I.

Why you shouldn't talk to the police if you are suspected of a crime.

This article is first in a three-part series written from an experienced criminal defense attorney’s perspective1 as to why no person, whether they be guilty or innocent, suspect, witness, or victim, should speak with the police without thoroughly considering the consequences which might arise from the interaction.2

This series of articles is not meant to be critical of the police. The target audience of this series is not a person who dislikes and distrusts the police. To the contrary, the target audience is a person who likes the police and believes that there is no reason to avoid speaking with the police.

I do not mean to disparage the police, or to disparage people who like and support the police. I intend only to educate people about the significant risks of talking with even the best-intentioned police officer in the officer’s professional capacity. The risks of speaking with the police are so significant that even experienced police officers might avoid speaking with the police.3

In Part I, we will explore why you should not speak with the police if you are suspected of a crime.

In Part II, we will consider whether you should speak to the police if you are a witness to a crime, or a victim of a crime.

In Part III, we will conclude by examining some situations when you should speak to the police.

So without further ado . . .

PART I. YOU SHOULD NOT SPEAK WITH THE POLICE IF YOU ARE SUSPECTED OF A CRIME.

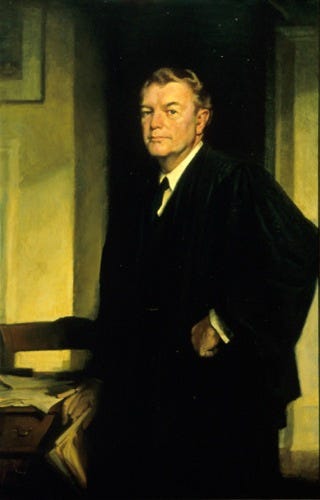

“Any lawyer worth his salt will tell the suspect in no uncertain terms to make no statement to the police under any circumstances.” -Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, concurrence, Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49, 59 (1949).

When confronted with an accusation of wrongdoing, most innocent people have a tendency to deny the accusation, or to try to explain what actually happened to the police. Even the guilty have a tendency to speak with the police, if only to deny their guilt, and to try to talk their way out of a potential criminal charge.

These instincts are natural, and they serve us well in most social encounters. Perhaps you are a slick talker, and you successfully talked yourself out of many bad situations in the past. Perhaps you talked your way out of an accusation levied by your high school guidance counselor or some other authority figure. Perhaps the police believed your story the last time you spoke with them. Perhaps you are truly innocent, and just want to help the police with their investigation. Especially if you are innocent, why would you avoid telling the police your side of the story?

Here are some good reasons why even an innocent person who likes the police should not speak with the police when they are the suspect of any crime:

Your statement to the police will not be admissible at trial if it is helpful to your case.

People who are unfamiliar with the rules of evidence tend to believe that if they tell their side of the story to the police, their statement can help them if they ever face a criminal trial. Unfortunately, this is simply not the case.

If you provide a statement to the police which might help your case at trial (and hurt the government’s case against you) that statement will typically not be admitted into evidence, and the jury will never hear about it. Under the rules of evidence, any statement made outside of the trial, if offered for the proof of the matter asserted, is subject to the rule against hearsay.4

Due to the rule against hearsay, if your defense lawyer tries to present your statement to the police as evidence favorable to you, a competent prosecutor will object to the admission of that statement, and the Judge will have no choice but to exclude the statement from evidence at trial.5 The jury can convict you without ever hearing about the exculpatory statement you made to the police.

Your statement to the police will be admissible at trial if it is hurtful to your case.

A reasonable person might think that if the defendant cannot introduce their statement at trial, then surely the prosecutor cannot use those same words against them. Not so fast. The rules of evidence are not equally applied to defendants and prosecutors in criminal cases.

Unlike a defense lawyer, a prosecutor can always introduce the words of a defendant at trial, so long as those words are relevant to the case. There are at least two exceptions to the hearsay rule which allow prosecutors to enter a defendant’s out-of-court statement against the accused: (1) Statement of Party Opponent6, and (2) Statement Against Self-Interest7.

Under the rules of evidence, your words can, and likely will be used against you at trial by the prosecutor. Conversely, your words cannot be used to help your case by your defense attorney. Under these circumstances, speaking with the police is a poor decision that will result in a significant disadvantage at your trial.

Speaking with the police cannot help you at trial, but it can certainly hurt you. Knowing this, why would you risk speaking with the police?

Any exaggeration, “white lie”, or omission in your statement can be used to convict you.

Even little white lies can hurt you. Don’t ever lie to the police. Better yet, don’t talk to the police in the first place. Photo credit: Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

Let’s say the police suspect you of a crime that you did not commit, and you decide to speak with them. The story you tell them is basically true, but you exaggerate some facts, or you leave out some embarrassing details, or you tell a “white lie” to the police. If the police have evidence that disproves any part of your statement, your likelihood of conviction at trial rises dramatically, even if your statement was otherwise true in every material way.

One of the oldest principles of our common law is the doctrine of “falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus.” For those of us who do not speak Latin, this is the premise that a person who lies about one thing can be presumed to be lying about everything.

For example, let’s say that you speak with the police about a murder that happened downtown, while you were uptown having a steamy affair with your coworker at a local hotel. You truthfully tell the police that you were not present during the crime, and you honestly answer all of their other questions. But when the police ask you where you were at the time of the crime, you tell them that you were at work, and fail to mention that you were actually sleeping with your coworker at the hotel.

You didn’t lie to the police because you were trying to cover up a murder. You just didn’t want anyone to find out that you were sleeping with your coworker to avoid embarrassment, or maybe to save your failing marriage.

But if the police find any evidence that you were not at work at the time of the murder, the reason for your false statement will not save you. At trial, the prosecutor will argue that you lied to the police and imply that an innocent person would not mislead the police. The prosecutor might ask the judge to issue a “consciousness of guilt” jury instruction, so the jury can deliberate whether your lie to the police was the product of a guilty mind.8

You might think that you will be able to explain your lie to the jury, and the jury will take mercy on you because everybody fudges the truth sometimes. But not so fast!

In order to explain why you lied, you will have to take the stand, and thereby subject yourself to the dangers of cross-examination.9 When you take the stand to testify, the jury’s opinion of you will be tainted, because they know that you already lied to the police. Why would they believe anything you say when they know you already lied to the police?

One of the most devastating lines that any prosecutor can say in their closing argument is: “The defendant has shown herself to be a liar. When she spoke with the police, she said ‘X’. But when she testified to you, she said ‘Y’. Was she lying to the police then, or was she lying to you now? Either way, you should consider why the defendant would lie to the police, and why she would lie to you. I suggest that the reason she lied is because she was trying to hide the fact that she committed the crime.”10

This is a devastating closing argument, and it is practically impossible for a defense lawyer to effectively refute.11 Practically any juror who hears this closing argument will be predisposed to convicting you.

If you simply refuse to speak with the police, the government cannot use any exaggerations, white lies, or omissions against you at trial. So why would you ever mislead the police and risk being convicted based on your dishonesty, when you can simply avoid the problem by refusing to speak with the police in the first place?

If you lie to the police, or if the police believe that you lied to them, you can be convicted of additional crimes based on your perceived dishonesty.

Never lie to the police. Never, ever lie to the police. Ever. It does not matter how slick your story might be. It does not matter how well you try to cover up your crime. If the police have any reason whatsoever to believe that you lied, your goose is cooked.

Not only will your statement be used to crucify you at trial for the crime you lied about, but you will face any number of additional charges for misleading the police. Based on your false statement, you might be charged with obstruction of justice, witness intimidation, or (depending on the situation) even perjury.

“It is almost always the cover-up rather than the event that causes trouble.” - Senator Howard Baker.

Using an example from above, let’s say that you told the police that you were at work during the commission of a murder, when in fact you were actually in a hotel room, engaged in a scandalous affair. As discussed above, this lie could be used to bolster the prosecution against you, and result in your conviction for the murder.

But let’s say you get lucky and avoid the murder conviction. Your lie to police will ensure that your legal troubles are far from over. In Massachusetts, you are likely to be charged with witness intimidation for misleading the police during the investigation. Witness intimidation is a felony that normally carries a maximum sentence of 10 years in state prison.12 But misleading the police during a murder investigation can result in 20 years of incarceration.13 If you are stupid enough to take the stand and lie during a murder trial, you will risk spending the rest of your life in prison.14 Is this a risk worth taking, when you can simply avoid speaking with the police in the first place?

The above argument presumes that you purposefully lied to the police. But what if you are truthful with the police? Can you guarantee that the police will believe your statement, and there is no way for them to discredit your words? What if the police believe that you are lying because there is insufficient physical evidence to support your story? What if your honest statement is refuted by other witnesses who lie for their own benefit?

Even if you are completely honest, you might be charged with obstruction of justice or witness intimidation simply because the police do not believe you. Why would you risk these additional charges when you can avoid them by simply refusing to speak with the police in the first place?

The police can lie to you without any repercussions.

As much trouble as you face when you lie to the police, the police are allowed to lie to you with few, if any repercussions.15 The premise that the police are allowed to lie to citizens might seem counterintuitive. After all, shouldn’t honesty be required of the police? Also, how is it fair that one participant in a conversation is allowed to lie, while the other participant faces severe criminal consequences for lying? Don’t be naive - the police are allowed to lie to you, and there is absolutely nothing you can do about it.16

The police are empowered to employ dishonest “ruses” to induce inculpatory statements from suspects.17 For example, the police are under no obligation to inform you that you are the suspect of a crime in the first place. The police can mislead you to believe that you failed a polygraph test when you actually didn’t.18 The police can falsely claim that they found physical evidence which incriminates you.19 The police can falsely tell you that they have video footage depicting you committing a crime.20 The police can falsely claim that your statement is “off the record”, when everything you say can be used against you.21 These are just a few examples of the countless ways that the police are allowed mislead you into confessing, whether you actually committed a crime or not.22

The police can mislead you without any repercussions, but any perceived dishonesty on your part results in devastating consequences. Does this seem like a fair arrangement to you? Why would you engage in a high-stakes conversation with an interrogator who can lie to you without any consequences? It should be obvious that the better choice is to simply avoid the conversation in the first place.

Even if you are innocent and you tell the truth, your statements to the police can still be used to convict you.

Let’s say that you speak with the police, and you provide a perfectly honest statement in support of your innocence. Without even knowing it, your statement might include a seemingly harmless fact or detail that will ultimately be used to support your conviction.

For example, let’s say that the police receive a report from a victim who was robbed on Elm Street. The robber was described as a very tall Caucasian male with light brown hair and blue eyes, who was wearing a black graphic t-shirt at the time of the robbery. The police suspect that you might be the robber because you are a white, 6’7” man with dirty-blonde hair and light blue-green eyes who lives in the neighborhood where the robbery took place.

The police ask you to come to the police station, and during the interview they ask some innocuous questions. Your conversation with the police goes something like this:

Officer: Were you on Elm Street any time today?

You: Yeah, I think I was there earlier, on my way to work.

Officer: Oh yeah? What do you do for a living?

You: Well, I’m actually an architect, but I was laid off a couple of months ago. So now I’m just picking up shifts at the supermarket to make ends meet.

Officer: Money is tight, huh?

You: Yeah. I’ve really been struggling, and the school year is about to start. I have no idea how I’m going to pay for my kid’s clothes.

Officer: I’m very sorry to hear that you’re going through hard times. I hope you get back on your feet soon!

You: Thanks, man. It’s really been a challenge. I kind of thought that you would give me a hard time here, but you’re alright.

Officer: Hey, don’t mention it. I’m just doing my job, you know? Say - Just out of curiosity, do you have any black t-shirts?

You: I have a couple of them. Actually my favorite shirt is a black t-shirt with this Linkin Park logo.

Officer: Oh? Cool! I like Linkin Park too. Thanks for agreeing to speak with me. We’ll be in touch if we need anything else. You’re free to go, and I hope you get back on your feet soon.

From your perspective, there is nothing incriminating in your statement. You were completely open and honest with the police, and you did not admit to any crimes.

But unbeknownst to you, later that day the police invite the robbery victim to undergo a photo array identification procedure at the police station. During this photo array, the police include your photograph among seven other similar-looking individuals. After carefully examining all of the photographs, the victim mistakenly identifies you as the perpetrator of the robbery.23

At your trial, the prosecutor will tell the jury that you admitted to being at the location of the robbery that day; you admitted that you were desperate for money because you lost your job; and you admitted that you own a black t-shirt similar to the one described by the victim.

Combined with the misidentification from the robbery victim, your own seemingly-harmless words can be used to convince a jury that you are guilty.

In this hypothetical you were honest with the police. Both you and the police officer were reasonable, polite, and courteous throughout your conversation. But nevertheless, you face prison time because you chose to speak with the police. Why take the risk?

Your statement to the police can be used against you if you “put your foot in your mouth”, or accidentally say things that you didn’t mean to say.

Let’s say you ignore my advice and speak with the police when you are suspected of a crime. Will you correctly tell your story, or will you put your foot in your mouth and accidentally implicate yourself in the crime? This isn’t as simple a question as it seems.

Most encounters between the police and suspects tend to be stressful events. The police might show up to your house when you were just in a major argument with your significant other, and you heart is still racing from the fight. Or you might speak with the police at the side of the road after a car accident. Or you might speak with the police in a claustrophobia-inducing windowless interview room at the local police department. None of these settings is conducive to clear thinking, or clear communication.

Imagine that during a conversation with the police at the scene of a car accident, you say something like “my brother and I went to the bar, and on our ride back home we got in a fight, and I smashed the car into a tree”. Well, you might think that you just told the innocent truth: You went to the bar (where you ate some empanadas and drank a diet Coke), then you verbally argued with your brother about a family dispute, and then the brakes on your car failed, causing you to crash into a tree.

But the specific words you used will be interpreted differently by the police. Your statement was vague enough so that a reasonable police officer is likely to believe that you (1) drove drunk after going to the bar, (2) physically assaulted your brother, and (3) negligently operated your car by crashing it into a tree.

The police officer will take pictures of your car wrapped around the tree, and your brother with bruises all over his face (which were actually caused by the car accident). The police will have all the physical evidence they need, and your own statement to confirm that you committed the crimes of Operating Under the Influence, Assault & Battery, and Negligent Operation.

When your case eventually gets to trial, your lawyer will have a hard time convincing the jury that you “accidentally” misspoke to the police officer. Your lawyer will squirm in front of the jury, explaining that when you went to the bar, you didn’t drink any alcohol; and that when you said you were “fighting” with your brother, you just meant that you were verbally arguing; and the reason your car smashed into a tree was due to faulty brakes.

If you had simply said nothing to the police, you would likely never be charged with a crime in the first place. But even if you were charged, the government would have a difficult time proving that you drove drunk, or that you hit your brother, or that you drove negligently. But since you decided to speak with the police and you put your foot in your mouth, you will be forced to hire an expensive lawyer, hire an even-more expensive accident reconstruction expert to testify about your faulty brakes, you will waste a lot of precious time in court, and you will potentially be convicted of three crimes that you did not commit.

Can you guarantee that you won’t accidentally put your foot in your mouth during a stressful encounter with the police? Can you guarantee that your words will not be misinterpreted? Why take this risk at all when you can simply refuse to speak with the police?

If you speak with the police, you might confess to a crime you did not commit.

What’s the harm in speaking with the police? It’s not like you’re going to admit to something you didn’t do! Or are you?

According to the Innocence Project, “[i]n approximately 25% of the wrongful convictions overturned with DNA evidence, defendants made false confessions, admissions or statements to law enforcement officials.”24

It might seem counterintuitive that a person would admit to a crime they didn’t commit. But reliable research in the field of false confessions indicates that a shocking number of convictions arise out of false confessions.25

The “Central Park Five” story perfectly illustrates the problem with false confessions. On April 20, 1989, the NYPD discovered an unconscious woman who had been assaulted while jogging in Central Park. The “Central Park Jogger” had been brutally raped and beaten. The “rape and attack was so severe, she lost 75 percent of her blood, suffering a severe skull fracture among other injuries.”26 Due to her head trauma, the victim retained no memory of the attack.

The vicious attack on the Central Park Jogger made international headlines, and ignited a media firestorm. Then-NYC Mayor Ed Koch called it “the crime of the century".27

NYPD identified a group of roughly 30 teenagers who were present in Central Park on the night of the crime. There was no evidence that these teenagers were responsible for the attack on the Central Park Jogger. Nevertheless, the teenagers were dubbed a “wolf pack” by the New York Daily News.28 “The New York Post’s Pete Hamill wrote that the teens hailed ‘from a world of crack, welfare, guns, knives, indifference and ignorance…a land with no fathers…to smash, hurt, rob, stomp, rape. The enemies were rich. The enemies were white.’”29 Former President Donald Trump took out full page ads in all of New York City’s major newspapers, with the headline “Bring Back The Death Penalty. Bring Back Our Police!”30

Five of the thirty teenagers were subjected to interrogation by the NYPD, and “[f]our of the five teens, all from Harlem, confessed on videotape following hours of interrogation. The boys later recanted and plead not guilty, saying their confessions had been coerced.”31

Yusef Salaam, who was 15 at the time of the incident, wrote in a Washington Post editorial that “[w]hen we were arrested, the police deprived us of food, drink or sleep for more than 24 hours . . . Under duress, we falsely confessed. Though we were innocent, we spent our formative years in prison, branded as rapists.”32

“Despite inconsistencies in their stories, no eye witnesses and no DNA evidence linking them to the crime, the five were convicted in two trials in 1990.”33 Three of the teenagers (Antron McCray, 15, Yusef Salaam, 15, and Raymond Santana, 14) were convicted of rape, assault, robbery, and riot. Kevin Richardson, 15, was convicted of attempted murder, rape, assault, and robbery. Korey Wise, 16, was convicted of sexual abuse, assault, and riot. They each spent between six and thirteen years in prison.34

In 2002, a serial rapist and murderer named Matias Reyes confessed that he was the true culprit of the attack on the Central Park Jogger.35 DNA evidence found at the crime scene confirmed that Reyes had actually committed this crime.36

The Central Park Five incident is just one of many stories involving false convictions arising from innocent people who spoke with the police while suspected of crimes. According to records compiled by University of Virginia Law Professor Brandon L. Garret, “more than 40 [people] have given confessions since 1976 that DNA evidence later showed were false”.37 These were just the cases that we know about, where DNA evidence was available to exonerate the falsely convicted. The total number of innocent people incarcerated due to false confessions is unknown.

Based on the story of the “Central Park Five”, one might assume that only abusive rogue cops are responsible for false confessions. But even well-meaning, professional police officers can make honest mistakes leading to a false confession.

“Jim Trainum, a former policeman who now advises police departments on training officers to avoid false confessions, explained that few of them intend to contaminate an interrogation or convict the innocent. ‘You become so fixated on ‘This is the right person, this is the guilty person’ that you tend to ignore everything else,’ he said. The problem with false confessions, he said, is ‘the wrong person is still out there, and he’s able to reoffend.’” The other problem with false confessions is that an innocent person is convicted, and loses years of their life due to the false confession.

The best way to avoid falling victim to a false confession is to simply avoid speaking to the police. So why would you risk making a false confession by agreeing to speak with the police?

There is no guarantee that your statement will be transcribed accurately in a police report.

If you choose to speak with the police, how can you guarantee that the police will accurately report your statement? If your statement is video or audio recorded, then at least you have some assurance that it will be accurately presented at your trial. But if your statement is not recorded, then there is no way to ensure that the police officer who took your statement will accurately testify about it in Court.

But why would a police officer testify inaccurately about your statement at a trial? Of course, the police officer might simply be an unethical rogue cop who lies under oath to strengthen his case against you. But the focus of this article is not on rogue cops, but on decent, professional officers who do everything in their power to present honest testimony.

So why would a decent, professional officer present false testimony about the statement you made to the police? There are several reasons that this might happen, and all of these reasons depend on the basic principle that police officers are human beings, just like everybody else.

Like all human beings, a police officer’s powers of perception and memory are imperfect. Perhaps the police officer simply mishears, misunderstands, or misinterprets your words. Perhaps she misremembers your words when she is called to testify at trial. All human beings are susceptible to imperfect perception and imperfect recollection.38 Even the most ethical police officer still has to contend with these common defects of perception and memory.

Encounters with suspects are often stressful for police officers. When the police encounter a suspect for the first time, particularly a suspect of a violent crime, they must be wary that the encounter might suddenly escalate into violence. Police officers are well aware that there are risks inherent to the job, including being killed in the line of duty during interactions with suspects.39

In 2022, police work was ranked 19th among the most dangerous jobs in America according to reporting based on the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.40 Some critics might argue that many occupations are substantially more dangerous than police work.41 But even these critics must concede that “only police officers face the threat of murder as a part of their job. No one is out trying to kill fisherman or loggers or garbage collectors.”42

In light of the dangers inherent in police interactions with suspects, it is perfectly understandable that such an interaction might be stressful for even the most professional police officer. Unfortunately, both memory43 and perception44 tend to be impaired in stressful situations. When faced with the stress of an interaction with a suspect, especially a suspect of a violent crime, it is understandable that a police officer might mishear, misunderstand, or misremember a suspect’s words.

Police officers typically draft police reports after their interaction with the suspect has been concluded. There is usually a time-lapse between an officer’s interaction with the suspect, and the completion of their police report. During that time, the police officer might take statements from other suspects or witnesses, or speak with other officers, or perform other important investigative duties. By the time the police officer types up the police report, it is impossible to guarantee that the suspect’s statement written in the report will accurately reflect the suspect’s actual words.

Police officers are not stenographers. Their reports rarely include a word-for-word quotation of a suspect’s statement. The suspect’s words are usually paraphrased in police reports. Even when direct quotations are provided, such quotations rarely include every single word that the suspect said during their interaction with the police. Even when a police report quotes every single word that a suspect uttered, the suspect’s tonality, emphasis, tempo, volume, body language, and other modes of subcommunication can easily lead to an inaccurate depiction of a suspect’s statement in a police report.

Consider the following quote, which one might find in a police report depicting a suspect’s statement about an allegation of domestic violence:

“She’s crazy. Sure I hit her.”

When you consider these words as written in a police report, they are a clear and unequivocal admission of guilt. But what if the suspect’s words included an emphasis on the word “crazy”, and the suspect uttered the word “sure” sarcastically, while rolling his eyes?

“She’s crazy. Suuuuure I hit her.”

Is this suspect’s statement actually an admission? Or is it actually a denial by a person who is frustrated by a false accusation, and relying on sarcasm to emphasize that the accusation is a lie?

As comedian Bill Burr hilariously noted in his 2019 standup special, Paper Tiger45, a statement can mean something very different than intended when “you go to court and you get a bad read”:

One of the primary purposes of a police report is to document facts that are necessary to issue a criminal complaint or indictment against a suspect. Police reports therefore tend to focus on inculpatory information, and give less attention to facts which the officer might not consider important enough to document. But facts which might not seem important through a police officer’s analytical lens might include crucially important information from the perspective of a defense attorney. When an officer reports only the inculpatory parts of a defendant’s statement, crucial contextual information may be left out of the report. At trial, a defendant will struggle to explain why the police officer’s testimony about her statement didn’t mention this contextual information.

The problems with capturing a defendant’s accurate statement in a police report are exacerbated by the passage of time between investigation and trial. In the author’s experience46, a criminal case typically takes between three to eighteen months to reach trial, depending on the complexity of the case, and the scheduling limitations of the Court docket. Particularly complex felony cases can take years to reach trial.

The longer it takes for case to reach trial, the less accurate an officer’s memory of her interaction with the suspect will become. Through the intervening months and years, a police officer might interact with dozens, if not hundreds of other suspects and witnesses. By the time that she is called to testify at trial, an officer might forget significant details of a particular suspect’s statement, or mistakenly attribute the words of a suspect in different case to the defendant in the case at bar.

Prior to taking the stand, police officers typically review their police reports to prepare for testimony. Even during trial, it is not unusual for police officers to forget important details of their investigations. In such circumstances, the Court will typically allow a prosecutor to refresh a testifying officer’s recollection by reviewing the police report.

But as noted above, there are plenty of reasons why a police report might not be an accurate depiction of the defendant’s actual statement. The defendant’s statement, as presented at trial by an investigating officer might differ substantially from the defendant’s actual words to the police.

If you speak with the police about a crime, there is no guarantee that the officer will accurately recite your statement at trial. Why would you risk being misquoted by a police officer at trial, when you can avoid that risk by simply refusing to speak with the police?

You cannot rely on a recorded statement to protect you from conviction.

A tape recording of your statement will not save you from a false conviction. Credit: Steven Weeks on Unsplash

If your truthful statement to police is audio or video recorded, then surely it can’t be misconstrued and used to convict you, right? By this point in the article, you should realize that it’s never that simple.

First, how can you be sure that your statement will actually be recorded and preserved until trial? Audiovisual equipment is not guaranteed to be perfect, and the quality of recording technology can vary widely between police departments. Some departments invest heavily in modern recording technology. Other departments might rely on ancient tape recorders due to financial constraints, or lack of technical expertise.

You might think that your statement will be recorded because your interviewing officer assures you that everything you say will be recorded. But is the interviewing officer the same person who installs and maintains the audiovisual recording equipment? Typically, the person responsible for installing, maintaining recording equipment is an IT specialist in the police department, and as every IT specialist knows, technology rarely operates without failure. Because audiovisual recording equipment can fail, and because recordings may be lost or inadvertently destroyed, you cannot rely on even the most honest officer’s representation that a recording of your interview will be available to you at trial.

If your interview is not properly recorded and maintained for trial, you will be stuck with all of the same problems that exist when you provide an unrecorded statement to the police. But those problems are likely to be exacerbated, because the officer might himself rely on the existence of a recording, and therefore expend less effort to accurately write down your words.

But what if the audiovisual recording equipment works as intended, and your statement is accurately played at trial. Even an accurate recording of your statement can present unnecessary risks at trial. Your statement will likely be recorded in a stressful interview environment. As a result of the stressful environment, you will be more likely to “put your foot in your mouth” or make potentially inculpatory mistakes in your statement. Armed with an audiovisual recording of that statement, the prosecutor will have irrefutable evidence of your misstatement at trial, and your defense attorney will have a hard time convincing the jury that you did not actually mean what you said during the recording.

Finally, if you decide to testify on your own behalf at trial, your testimony will be subject to all of the same memory flaws that befuddle every human mind.47 By the time you testify at trial, a year or more might have passed since your statement was recorded. What is the likelihood that your memory, under the stress of trial testimony, will exactly replicate the recorded statement you provided to the police a year or more prior to the trial?

If your memory fails you at trial, and your testimony does not exactly match the recorded statement you made to the police, the prosecutor will pounce on every disparity between your testimony and the recorded statement, and paint those disparities as lies. These disparities will be used to discredit your testimony at trial, and to imply that your apparent dishonesty depicts your “consciousness of guilt”.48

You cannot rely on a recording of your interview because you cannot predict whether the interview will be properly recorded or preserved for trial. If your interview is recorded, any misstatements during that interview will be preserved forever. Even if the recording is preserved for trial, and it depicts your true statement, any discrepancies between the recording and your trial testimony due to imperfect recollection will make you look like a liar at trial. Why take these risks when you can simply refuse to speak with the police?

Invocation of Miranda rights may not protect you from your statements being used against you at trial.

In theory, there is an important exception to the general rule that a suspect’s words to the police can be used against the suspect at trial. If a defendant’s words are obtained as a result of custodial interrogation after the defendant unequivocally invoked their Miranda rights, any statements made after the Miranda invocation should be inadmissible at trial.

But suspects should not presume that Miranda will protect their statements from being admitted at trial. There are many exceptions to the Miranda rule which are confusing to anyone who has not been formally trained in criminal law. Some of these exceptions are counterintuitive, and a lay person who believes that they invoked their Miranda rights might be surprised to learn that their statements can actually be used against them at trial.

For example, you might tell the police that you do not wish to speak with them, and you want a lawyer to be present. But if your statement is obtained in a “non-custodial” environment, your invocation of Miranda rights will not protect you.49 If the police approach you on your porch, and you tell the police that you intend to get a lawyer, and will not speak with them without one, but you accidentally blurt out some incriminating words during the conversation, those words will be admissible against you because they were not the product of police interrogation, and they were uttered in a non-custodial environment.

But this limitation on Miranda doesn’t just apply to statements made on your porch, or on the street. Counterintuitively, there are situations where even statements made inside a police station50 or in a jail51 are considered non-custodial statements.

Even when you intend to rely on Miranda rights during custodial interrogation, you might still fail to properly preserve those rights if you don’t say the right “magic words”. For example, if you say “I think I want a lawyer before I say anything else”, you might believe that you have invoked your right counsel prior to speaking with the police. But according to the U.S. Supreme Court, you would be wrong.52

Similarly, if you stay completely silent, and refuse to answer any questions that the police ask you after being read Miranda rights, but you say something to the police three hours later, Miranda will not protect your statements from being used against you at trial.53

Because the caselaw around Miranda is a confusing mess for anyone who hasn’t been formally trained in criminal law, it is difficult for any lay person to know whether their statement to police might be used against them, even if they ask for a lawyer, and even if they say they don’t want to speak with the police, and even if they say nothing at all for several hours while in police custody.

The only way to reliably protect your words from being used against you at trial is to respectfully, but loudly, clearly, and unequivocally say a close variation of the following phrase: “I am invoking my 5th Amendment right against self-incrimination, and my 6th Amendment right to counsel. I respectfully refuse to speak to you, or any other officer without my attorney present.”54 Then, say nothing at all to the police unless and until you are released, or an attorney shows up to assist you.

Your statements to the police might be used against you at trial, even if they are involuntary.

If you are suspected of a crime and wind up in police custody, any decent police officer will treat you with the dignity and respect due to a citizen who is presumed to be innocent. But unfortunately, not all police officers are decent. Like any group of human beings, the ranks of the police include many wonderful people, but they also include some outliers of questionable moral character.55

Let’s say you got very unlucky because the police officers who arrested you were rogue cops who physically or psychologically abused you to obtain an involuntary confession. Did they beat you and smash your teeth by forcing a broomstick down your mouth after anally raping you with that broomstick?56 Did they take advantage of your young age and mental deficiency to obtain your confession?57 Well if you live if Massachusetts, then you are in luck!

You might never recover from the physical or psychological injuries inflicted on you by rogue cops. You might wake up screaming every single night for the rest of your life, and experience crippling panic attacks every time you hear police sirens. But in Massachusetts at least your coerced confession can’t be used against you when the government takes you to trial!

In Massachusetts, we have the “humane practice rule” to spare you from being treated like a human piñata by rogue cops and later being convicted with your involuntary confession, so that you can face further physical and psychological torture as a ward of the Massachusetts Bureau of Prisons.58 Now that is progress!

The Massachusetts “humane practice rule” prevents the government from introducing statements and confessions obtained from defendants involuntarily.59 Similar to the Massachusetts “humane practice rule”, Federal law includes a “voluntariness doctrine” under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, which (in theory) requires exclusion of involuntary confessions from trial.60

But in spite of these protective legal doctrines, there are many cases where the police obtain “confessions” from defendants whose ability to competently assert their Miranda rights is compromised, and these “confessions” are used to convict innocent people.61

One noteworthy example is the case of Brendan Dassey, a developmentally-challenged 16-year-old, whose questionable “confession” was the subject of the Netflix series, “Making a Murderer”.62 Dassey “confessed” after being interrogated four times, over a 48-hour period, with no access to a lawyer63, parent, or other interested adult. Dassey has a borderline-deficient IQ, and he was clinically evaluated as being highly suggestible, and prone to providing false confessions under pressure. Dassey was interviewed by police officers who employed the “Reid technique”, an interrogation strategy which has been criticized as “inherently coercive” by experts in forensic psychology.64

The video of Brendan Dassey’s so-called “confession” shocked the world and won the producers of “Making a Murderer” a Primetime Emmy Award. Despite global attention to this injustice, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Dassey’s conviction, and found that the police properly obtained Brendan Dassey’s confession.65 In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to grant certiorari to review the Seventh Circuit’s decision.

Despite the unfairness inherent in Brendan Dassey’s case, and the strong possibility that his “confession” was unreliable, Brendan Dassey was sentenced as an adult for his alleged participation as an accessory to rape and murder. Brendan Dassey will not be eligible for parole until 2048.

The Massachusetts “humane practice” doctrine is a more defendant-friendly standard than the Federal “voluntariness doctrine”. In Massachusetts, unlike in many other States, a statement may be considered involuntary even when the police do no wrong. The focus of the “humane practice” doctrine is on the mental state of the defendant, and not the actions of the police. The logic of the doctrine is that no person should be convicted based on a false confession simply because they made a statement while their mind was impaired.66

But even the Massachusetts “humane practice” doctrine fails to provide protection for most defendants who speak to the police while their mind is impaired. For example, police officers found Steven Chrispin on the side of the road in Sudbury, MA at 2:00AM on December 19, 2010.67 Chrispin had just been in a serious car accident. His Jeep Cherokee struck a telephone pole so hard that it knocked over the pole. When police arrived at the scene, Chrispin was standing in the roadway in his socks, and he was unsteady on his feet.

When approached by police, Chrispin admitted that he was “going too fast”, and that he “had too much too drink”. The Massachusetts Appeals Court found that even though Chrispin had been “shaken” by the collision, and was clearly intoxicated, “there [was] no reason to doubt whether his statements were the product of a rational intellect.” In other words, Chrispin was far too drunk to operate a motor vehicle, but he was not so drunk as to prevent his statements from being considered involuntary.

In summation, whether you are suffering from a mental illness, or you are a child with IQ deficiencies, or you are under the influence of a mind-altering substance, there is a substantial risk that statements you make to the police will be used against you at a criminal trial, despite the legal doctrines that exist to protect defendants from involuntary confessions.

Even if you want to confess to a crime, you will always have a better opportunity to confess with the assistance of legal counsel.

But what if you want to confess to a crime? There are many good reasons why a person might want to confess to a crime. Perhaps the guilt of the crime is weighing heavily on your soul, and you want to take responsibility for your actions. Perhaps you rather come clean about your crime than live under a dark cloud of suspicion for the rest of your life. Perhaps you believe that your crime will inevitably be discovered, and you will earn some leniency by admitting to the crime before it is uncovered. Perhaps you want to confess because someone else was falsely accused of the crime you committed, and you do not want to see injustice done to an innocent person. Perhaps you are just an honest person who made a criminal mistake, and you do not wish to hide from the consequences of your actions. There are countless other good reasons which might compel you to take responsibility for a crime that you committed.

Even if you want to confess, and you have good reasons to confess, you should still avoid speaking with the police before discussing your confession with an experienced criminal defense attorney. Whatever your reasons for confessing, you would be foolish to confess without first ensuring that your confession is properly credited by the government, and the judge who will ultimately sentence you for the crime you confessed to committing.

When a person confesses without counsel, they do not have the requisite experience with the criminal justice system to truly understand the consequences of their confession. The police are under no obligation to disclose the possible consequences of your confession to you. Only your lawyer, who has your best interests in mind, can reliably inform you of the rights you might waive by confessing. Only your lawyer can protect you from a confession which gives rise to a disproportionately harsh punishment, or to consequences which you might not foresee.

Consider the following examples of well-intentioned confessions which could be prevented through the intervention of a criminal defense attorney:

Example 168: Let’s say you want to confess to a crime that you believe is relatively minor: Your boyfriend cheated on you, and in a moment of heartbreak you “dug a key into the side of his pretty little souped-up four-wheel drive, and carved your name into his leather seats”.69 Let’s say you want to get the incident out of the way, and confess that you damaged that dirtbag’s car to the police. What could go wrong? Didn’t Carrie Underwood do the same thing? Won’t the police understand that you were the real victim in this incident?

I’m sorry to tell you this, but you ain’t Carrie Underwood.70 In Massachusetts, the “minor” crime you committed is both a Vandalism and Malicious Damage to a Motor Vehicle. In Massachusetts, Vandalism is a felony which carries up to three years’ state imprisonment. Malicious Damage to a Motor Vehicle is a felony which carries up to 15 years’ state imprisonment. A prosecution for Malicious Damage to a Motor Vehicle cannot be placed on file, or continued without a finding, essentially requiring you to become a felon upon conviction. Still think that you committed to a “relatively minor” crime? If you confess to this crime without first consulting with an attorney, you might quickly regret speaking with the police.

Example 2: Let’s say that your son is charged with carrying a firearm without a license71 after the police found him shooting some empty cans in your backyard. You know that you foolishly left the gun unsecured on your kitchen table after a hunting trip. You might believe that if you admit to the police that you are responsible for your son obtaining your firearm, your admission will save your son from being prosecuted.

But your confession will do absolutely nothing to help your son. In fact, the government does not need to prove how your son obtained the firearm to convict him of carrying it without a license. Not only will your confession do nothing to help your son, but you will also face a criminal conviction for unlawful storage of the firearm, resulting in up to 1.5 years of incarceration.72 Your confession does nothing to help your son, except ensure that his parent will also face incarceration.

Example 3: Let’s say that you have a drug problem, and you are pulled over while driving in a car with four friends along with a duffel bag full of cocaine. Believing that you can help your friends avoid prosecution, you freely admit to the police that all of the cocaine belongs to you. Perhaps the cocaine was meant to be split five-ways, or perhaps the cocaine actually does belong solely to you.

Regardless of your admission, the police are still likely to charge you, along with your friends for trafficking in cocaine under a constructive possession theory.73 If you had said nothing at all, the government might have a hard time proving that the cocaine belonged to anyone in the car, and the cases against everyone might be dismissed.74 But your admission to possession of the cocaine will provide ample evidence to convict you of drug trafficking, while doing nothing to assist your friends.

Countless examples of misguided confessions can be provided. The common thread between such examples is that suspects who speak with the police without first consulting with an experienced attorney do so at their peril. They might have good, principled reasons to admit to their crimes, but their admissions are likely to come with unintended consequences that a simple legal consultation would prevent.

Finally, even if confessing to a crime is the right thing to do, and even if you fully understand and appreciate the consequences of your confession, the circumstances of your confession are crucial to obtaining a just outcome in your case.

You will always have an opportunity to confess to a crime, so why offer the confession under circumstances that will result in devastating consequences which can be avoided? If you intend to confess to your crime, allow that confession to aid you in securing the best sentence possible through negotiation between your attorney and the government.

At a bare minimum, an experienced defense attorney will negotiate the terms of your confession as part of a plea agreement. The vast majority of criminal cases in the United States are resolved through plea agreements.75 When you accept responsibility for your crime, your candor and honesty should be reflected in the sentence that you serve.

But how can you guarantee that your confession will result in a fair resolution of your case if you already told the police that you are guilty without any consideration from the government? If you confess to a crime prior to consulting with a defense attorney, you will handicap your lawyer’s ability to negotiate a fair plea agreement in your case. If you are going to confess, you should at least make sure that your confession is properly credited in your eventual plea agreement.

Conclusion: Don’t Speak With the Police if You are Suspected of a Crime.

This article only scratches the surface of potential reasons why “[a]ny lawyer worth his salt will tell the suspect in no uncertain terms to make no statement to the police under any circumstances.”76

Of course there are good reasons to speak with the police, and such reasons will be explored in Part III of this series of articles. But the reasons to avoid speaking with the police are substantial, and any person who knows that they are suspected of a crime should avoid speaking with the police at all costs.

Can you think of any other good reasons to avoid speaking with the police? Do you disagree with these reasons? Leave a comment below, and let’s begin a discussion about this important subject.

Please share this article with anyone who you think might be interested.

To be continued in Part II: Should You Talk to the Police if You are the Victim or Witness of a Crime.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article, and I look forward to hearing from you. -Joseph Zlatnik, Esq.

Mandatory disclaimer: This article is an opinion of the author, and it is provided for educational purposes only. The author is an experienced, licensed criminal defense attorney in Massachusetts, and his knowledge applies only to the laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and relevant Federal laws. The law may differ in other jurisdictions. You should not act in reliance of this article or consider it “legal advice”.

The author does not intend to create any form of attorney-client relationship between the author and any reader. If you are accused of any crime, you should immediately seek the advice of a qualified criminal defense attorney who is experienced in the practice of criminal law within your jurisdiction.

If you are accused of any crime in Western Massachusetts, do not hesitate to contact the author for a formal legal consultation.

Of course there are many situations when it is not only appropriate, but actually imperative to speak with the police. The purpose of this article is to illustrate the risks that individuals take when they speak with the police. These risks must be weighed against other, potentially more significant risks. If your life or your safety (or the life or safety of any other person) is in danger, do not hesitate to call the police for help.

Officer George Bruch of the Virginia Beach Police Department offered an excellent lecture at Regent University School of Law about why he would never speak with other police officers if he was suspected of a crime. Available at YouTube.

See Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 802.

Of course there are many exceptions to the rule against hearsay. Unfortunately, in most contexts, the self-serving statement of a defendant on trial, previously offered to the police during an investigation will rarely involve one of these exceptions.

See Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 801(d)(2).

See Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 804(b)(3).

See Massachusetts Criminal Model Jury Instruction no. 3.580, Consciousness of Guilt (2009 Ed.) (“You have heard evidence suggesting that the defendant . . . may have intentionally made certain false statements before, during, or after his or her arrest . . . If the Commonwealth has proved that the defendant made false statements, you may consider whether such actions indicate feelings of guilt by the defendant and whether, in turn, such feelings of guilt might tend to show actual guilt on this charge.”).

The dangers of taking the stand require significant analysis, and they are beyond the scope of this article. The author might discuss the dangers of presenting a defendant's testimony in a future article.

To pedantic lawyers who might read this article: I am aware that this closing statement might draw an objection. But some variation of this closing statement is permissible, and every experienced criminal lawyer has used a similar statement about a witness with credibility issues. I’m simply using the clear language to demonstrate the devastating effect of prior inconsistent statements on a jury.

The difficulty for a defense lawyer to refute a powerful closing argument from the Commonwealth is even greater in jurisdictions like Massachusetts, where the Commonwealth gets the “final word” in its closing statement, and the defense has no opportunity for rebuttal.

M.G.L. c. 268, sec. 13B.

Id.

M.G.L. c. 268, sec. 1.

See, e.g., Frazier v. Cupp, 394 U.S. 731 (1969).

See id;

See Kassin, Saul, “Law Enforcement Experts on Why Police Shouldn’t be Allowed to Lie to Suspects”, Time Magazine (Dec. 16, 2022). Available at Time Magazine.

See “The False Confession of Peter Reilly”, Psych 424 Blog, Penn State (2019). Available at Penn State.

Warden, Rob, “Gary Gauger”, The National Registry of Exonerations, University of Michigan School of Law (2020). Available at The National Registry of Exonerations.

See McKinley, James C., Jr., “Sexual Abuse Case Dropped Against Intern at Preschool”, The New York Times (2014). Available at The New York Times.

See Commonwealth v. Tremblay, 460 Mass. 199 (2011).

See fn. 17, supra.

Witness misidentification is the single greatest source of false criminal convictions. Readers interested in the subject of witness misidentification should review the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Study Group on Eyewitness Evidence: Report and Recommendation to the Justices (July 25, 2013). Available at SJC Eyewitness Study Group Report.

“False Confessions Happen More Than We Think”, Innocence Project (Mar. 14, 2011). Available at Innocence Project.

See Shwartz, John, “Confessing to Crime, but Innocent”, The New York Times (Sept. 13, 2010). Available at The New York Times.

“The Central Park Five”, History.com (Sept. 23, 2019). Available at History.com.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Salaam, Yusef, “I’m One of the Central Park Five. Donald Trump Won’t Leave Me Alone.” The Washington Post (Oct. 12, 2016). Available at The Washington Post.

Supra at fn. 15.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Supra at fn. 14.

Although outside the scope of this article, the imperfections of human memory and perception are well established in the field of forensic psychology. The reader is urged to review the work of Dr. Elizabeth L. Loftus, whose contributions to the science of memory and perception cannot be overstated.

The reader is encouraged to visit the Officer Down Memorial Page to understand the gravity of risks faced by police officers in the line of duty. Available at ODMP.org.

Gornstein, Leslie, “The 31 Deadliest Jobs in America in 2022, Ranked”, CBS News (June 27, 2022). Available at CBS News.

See Fleetwood, Blake, “Police Work Isn’t as Dangerous as You May Think”, Huffington Post (Dec. 6, 2017). Available at Huffington Post.

Id.

See Luethi, et al., “Stress Effects on Working Memory, Explicit Memory, and Implicit Memory for Neutral and Emotional Stimuli in Healthy Men”, Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience (Jan. 15, 2009) (“A pronounced working memory deficit was associated with exposure to stress.”).

See Ramsland, Katherine, “Perception Under Pressure: Survival Situations in Police Work Change their Perceptual Frames”, Psychology Today (Feb. 13, 2020). Available at Psychology Today.

The author practices law in Western Massachusetts. The period of time it takes to take a criminal case to trial can vary drastically between jurisdictions.

See fn. 32, supra.

See fn. 8, supra.

See, e.g., Oregon v. Mathiason, 429 U.S. 492 (1977).

Id.

See Illinois v. Perkins, 496 U.S. 292 (1990).

Davis v. United States, 512 U.S. 452 (1994) ("I think I want a lawyer before I say anything else" deemed to be an ambiguous invocation of the right to counsel, and statements made thereafter deemed admissible, despite the absence of a lawyer.)

Berghuis v. Thompkins, 560 U.S. 370 (2010).

Even if you say these “magic words” however, how will you prove that you said them? If your Miranda invocation is tape recorded in a police interview room, or if the police officer is equipped with a functioning body camera (equipped for audio), you will at least have evidence of your unequivocal Miranda invocation. But if you invoke your Miranda rights under circumstances where they are not recorded, you will only have your own word, and (hopefully) the good faith of an honest police officer to prove that you invoked your Mirana rights. One does not need a wild imagination to conceive of a situation where an unethical police officer might deny that a suspect unequivocally invoked their Miranda rights, and the suspect’s self-serving claim to the contrary might not be credited by the Court.

The purpose of this article is not to attack the police. Nevertheless, when it comes to the subject of coerced and involuntary confessions, one cannot appropriately analyze the issues without providing examples of police misconduct.

Referring to the torture of Abner Louima at the hands of the NYPD. See, e.g., O’Grady, Jim & Fertig, Beth, “Twenty Years Later: The Police Assault on Abner Louima and What it Means”, WNYC News (Aug. 9, 2017). Available at WNYC.org.

Referring to the coerced confession of Brendan Dassey, a developmentally-challenged 16-year-old, at the hands of Manitowoc County, WI police. See, e.g., Ricciardi, Laura & Demos, Moira, “Making a Murderer”, Netflix (2015). Available at Netflix.

See “Dozens of suicides, guard attacks and a pedophile priest murdered in his own cell: The bloody history of the prison where Aaron Hernandez hanged himself”, The Daily Mail (Apr. 19, 2017). Available at The Daily Mail; Rezendes, Michael, "New scrutiny for Bridgewater State Hospital after complaints”, The Boston Globe (Apr. 17, 2014). Available at The Boston Globe.

See Commonwealth v. Tavares, 385 Mass. 140, 149-153 (1982).

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1936).

See supra at fn. 13, 14 & 15.

As much criticism as the police received for their interrogation of Brandon Dassey, the most odious figure in “Making a Murderer” was not a police officer. Dassey’s court-appointed lawyer, Len Kachinsky, received scathing criticism from the public and the criminal defense bar for abandoning his vulnerable client during the interrogation. See Mueller, Chris & Thompson, Andy, “Len Kachinsky, Reviled for His Brief Representation of Brendan Dassey, Continues to Attract Attention in Wake of 'Making A Murderer'”, Appelton Post-Cresent (Sept. 11, 2020) (“[Kachinsky] was called, among other things, a ‘disgusting human being,’ a ‘pure disgrace to the Wisconsin judicial system’ and a man with a ‘sickened soul.’”).

See Starr, Douglas, “The Interview: Do Police Interrogation Techniques Produce False Confessions”, The New Yorker (Dec. 1, 2013). Available at The New Yorker.

Brendan Dassey v. Michael A. Dittman, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, No. 16-3397 (2017). Available at Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

See Commonwealth v. Chung, 378 Mass. 451, 457 (1979) (“If the defendant comes forward with evidence of insanity at the time of his confession, the judge is obliged initially to determine whether the statements given were the product of a rational intellect as part of the issue of voluntariness.”).

Commonwealth v. Chrispin, 2013 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 967 (2013).

All examples are derived from Massachusetts law. Different legal standards might apply in your jurisdiction.

Underwood, Carrie, “Before He Cheats”, Some Hearts, FAME, Muscle Shoals, Alabama (2005).

If you actually are Carrie Underwood, thank you for reading my article! Don’t hesitate to contact me. I’m a huge fan!

M.G.L. c. 269, sec. 10(a).

M.G.L. c. 140, sec. 131L.

See “Constructive Possession”, Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School (2022). Available at Legal Information Institute.

See, e.g., Commonwealth v. Reyes, 98 Mass. App. Ct. 797 (2020) (“[M]ere presence in the area where contraband is found is insufficient to show ‘the requisite knowledge, power, or intention to exercise control over the [contraband], but presence, supplemented by other incriminating evidence, will serve to tip the scale in favor of sufficiency.’”) (citations omitted).

Johnson, Carrie, “The Vast Majority of Criminal Cases End in Plea Bargains, a New Report Finds”, NPR (Feb. 22, 2023)(“In any given year, 98% of criminal cases in the federal courts end with a plea bargain”). Available at NPR.

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49, 59 (1949) (concurring opinion of Hon. Robert H. Jackson).